Homeownership dream turning into a fantasy

Build for a future and not just roofs.

Home ownership is the most important factor for stability, and that leads to family choices, community well-being and wealth generation – the primary driver for wealth accumulation for most Canadians. It is a fundamental part of our society. However, home ownership as a possibility is slipping away from more and more Canadians.

From 2011 to 2021, the latest 10-year census data, the number of Canadians who are renting has grown by 22%. Over the same period, home ownership has only grown by 8%. In other words, renting is increasing almost three times faster than home ownership. 33.1% of Canadians are living in rented accommodations.

Over 40% of homes built between 2016 and 2021 are occupied by renters. In Quebec 61.3% of new homes are rented. Since 2016, 40.4% of new dwellings are rented. That is the 2nd highest percentage since the 1960s.

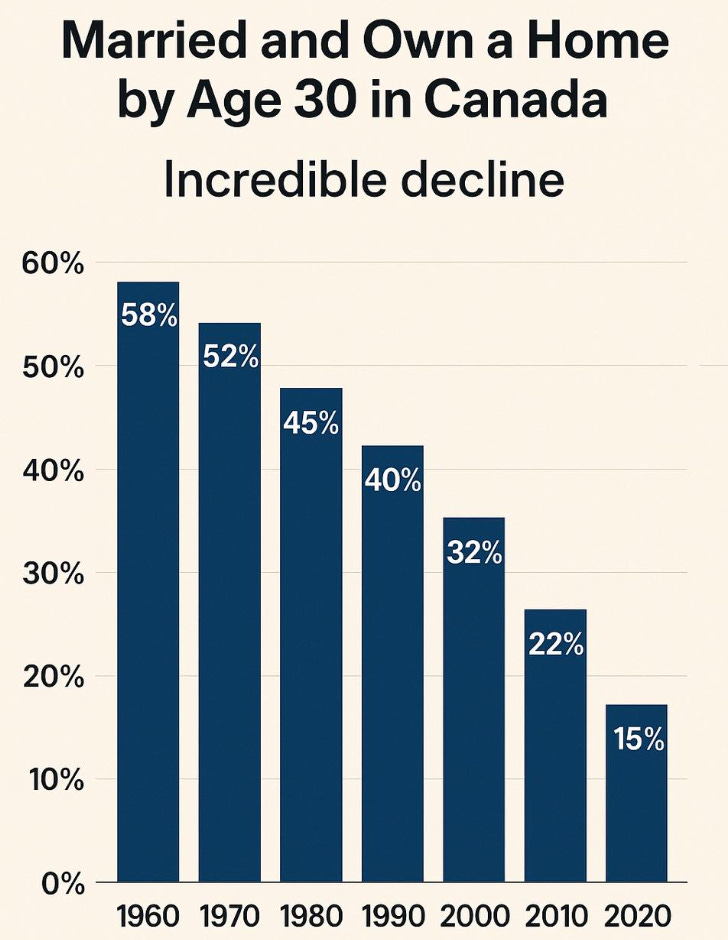

Young people are leading the rental growth with 80% of 25-29 year olds rent, 60% of 30-34 year olds and around 50% of 35-39 olds. Home ownership is fading away from the next generation and has been declining since the Boomer generation.

Based on demographics, home ownership has been slowly declining in Canada for decades. The problem is getting so big that we are just now noticing it at a policy and public discourse level.

The median age of a renter in Canada is 32, and is getting older. In the more expensive areas in Canada, like Vancouver or Toronto, the median age of a renter is over 34. 12% are with children. This should tell you that having children for people who rent is a much harder consideration, and really not a surprise. This is, and general unaffordability is a primary driver for the decline in Canadians having kids. So if we want Canadians to have kids then they need to feel secure about their housing situation first.

Renting used to be a stepping stone to ownership, but because of soaring rent costs, long-term renting is surging and becoming the new norm. The average renter is spending 38.6% of their income on rent and debt payments. 15% of renters spend more than half of their income on rent. The average renter’s credit score is declining, and that is because more renters are squeezed to take on debt just to survive after paying for rent.

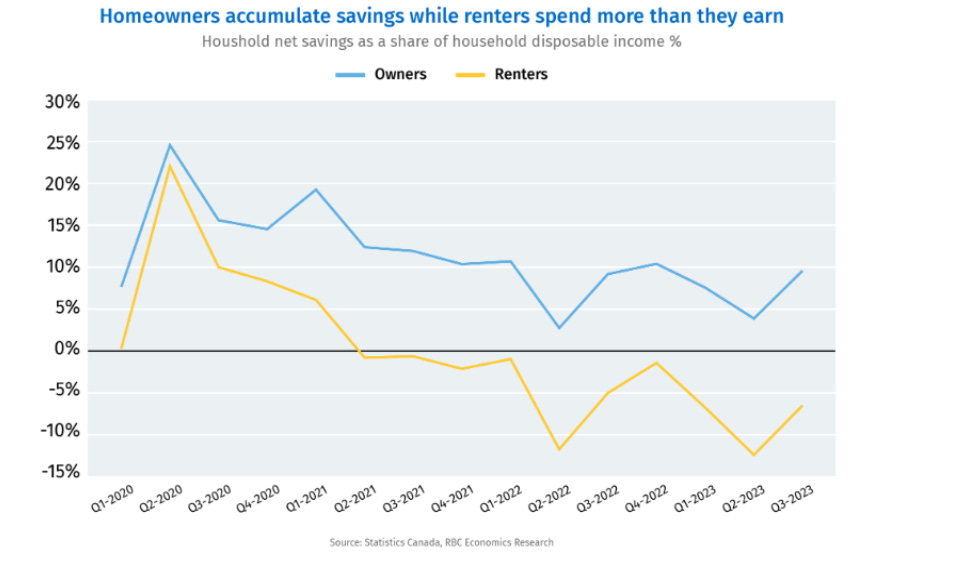

This puts renters in the worst financial position as a demographic, on average, in Canada. Credit card and auto loan payments arrears are growing faster in renters. This means a bigger and growing percentage of Canadians have the inability to grow wealth and have declining or negative saving rates.

The housing crisis fueled by mass immigration, was one of the worst policies for Canadians’ financial health. It separated the country into 2 classes: homeowners whose net worth and savings went up and driven by the scarcity of housing, and the people who were on the other side of the coin and got a double-digit increase in shelter costs every year for a number of years.

This artificial short-term boost put Canada’s overall economy at risk as it decreased discretionary spending. Discretionary spending is a key part of GDP’s total economic output. It drives consumer demand, supports local businesses thus employment, etc. This is in part why we see so many small businesses struggle, and employment in the private sector isn’t as robust. The hiring and wage growth in the public sector is masking serious issues.

As we know, compounding is one of the most important aspects of wealth growth, which means time is a key component in wealth growth, next to the saving rate. The years record Canadians couldn’t save will further create divergence in financial stability amongst Canadians.

The other big hurdle facing renters in entering homeownership that isn’t talked about is home choices. Over the last couple of decades, dwelling construction has moved definitively from single-detached to multi-unit.

This multi-unit dwelling boom is a bad knee-jerk reaction to another bad policy. We are creating scarcity, again, in one housing option and lately have been making it even worse with the blanket upzoning policies that reward developers with taxpayer dollars for taking down beautiful single detached lots and shoving as many dwellings into it as possible with zero consideration to anything else.

Often, multi-unit dwellings such as condos or townhouses come with condo fees, and that additional hard cost shrinks how much in mortgage people can take on. This leads to further erosion of homeownership affordability and when Canadians can actually afford a home it is a much less of a home than any generation beforehand.

I also have to point out that the transition to multi-unit homeownership vs detached homeownership puts it at a higher risk. Unlike with detached single homeownership, which comes with land and much more flexibility, a multi-unit dwelling has less flexibility, shorter life span and is dependent on everyone else, with a guaranteed increase in condo fees.

All of the above has led to the average age of first-time home buyers (and home buyers in general) to climb up, and that has a societal transformational impact. As people take longer to save for a home, they save less for retirement. As they are older when they buy a home, it takes them into the later years to pay it off, and this impacts the having kids dilemma, again.

There is some good news on the horizon with house prices starting to drop because of the slowdown in mass immigration, and credit exhaustion, which leads to fewer buyers. Rent prices are also coming down with less demand and a substantial increase in rental-focused construction.

We need to remove ideological short-term thinking from our neighbourhood development and multi-unit focus and start building single detached homes again to give Canadians an option that promotes family growth, and not turn that into a class.

Canada needs to develop more economically viable locations to live in to help reduce concentration into a handful of cities that drive inefficient demand. Regional and rural economic growth is such low-hanging fruit in Canada, and being the 2nd largest country in the world, it only makes sense to use what we have.

We need to restore the flow of capital from developers and bondholders back to Canadians’ pockets and our local economies.

It is imperative to re-focus on economically sound policies that promote long-term housing affordability for Canadians to build our society on, and not price Canadians out of Canada.