Canada's healthcare is a data problem

Improvements will come from being better informed.

One of the hardest parts of writing articles about Canada’s healthcare is how bad the data is. Underreported, poorly reported, not quantified properly, some places don't report some data and it goes on. Our biggest issue is not having a clear picture of what is going on in our healthcare system.

National data standards should be required by all provinces and territories for reporting and publication. There is no way of making educated decisions, assumptions, or investments otherwise. Right now, it’s all just guesstimations to a certain degree.

I’ll give the Liberal Party credit here as they tried (and are still kind of trying) to tie the increase in Canada Health Transfers to Provinces in the recent negotiations to creating a common data and indicator system for Canada.

Canada has dozens of health regions aka health authorities and this fragmentation without unity in data, analytics, and best practices sharing reduces clarity to needs and trends. This lack of clarity is why Canada’s healthcare is in such turmoil. It is because we are constantly playing catch-up rather than leading with precise intent and focus.

Every day, especially around election time, there are buzzword promises for our healthcare system. If you notice none of them are specific but we need to throw more money at something. Usually staffing but we have no idea who we need, where, and why. Just more.

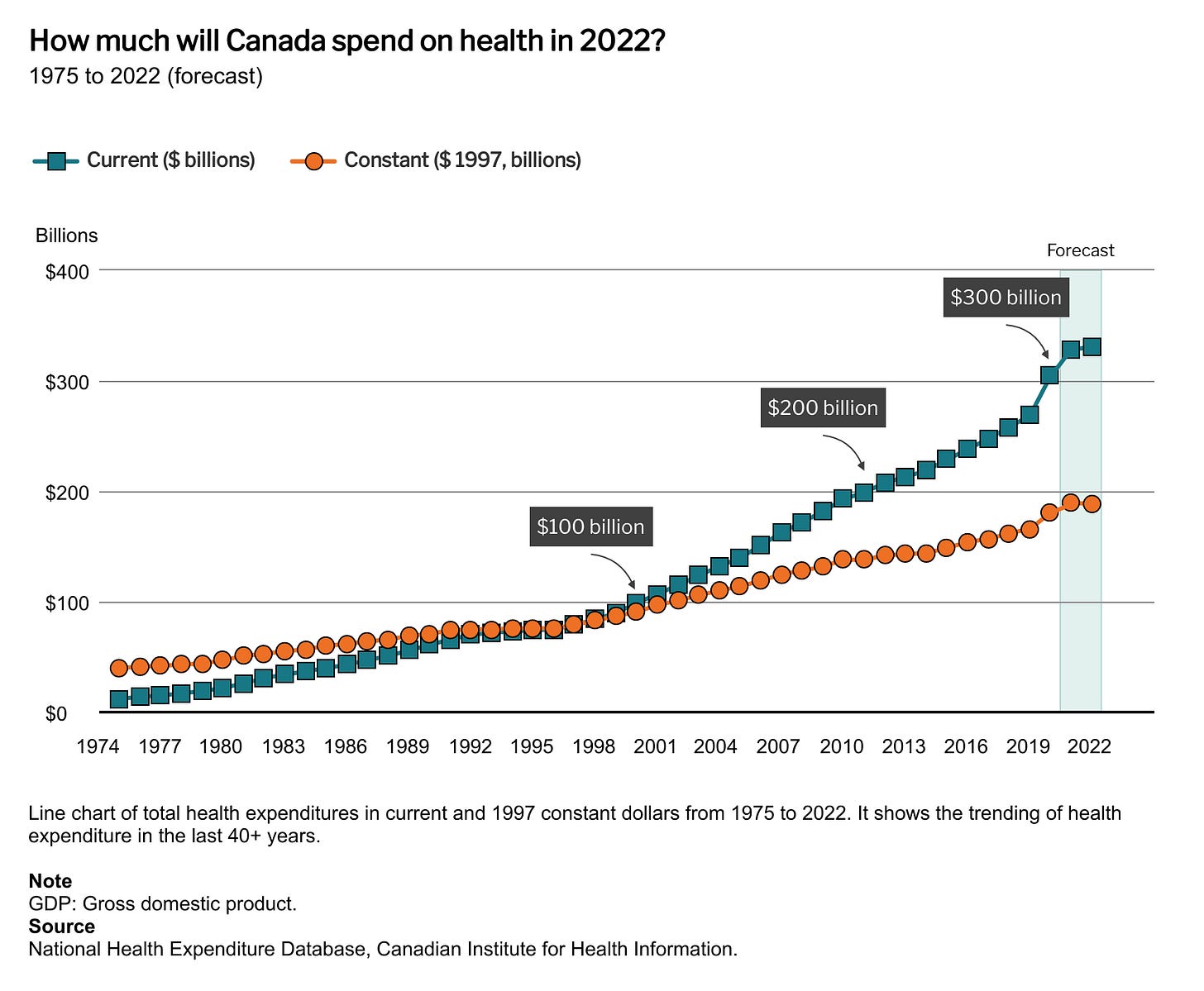

Canada spends roughly $330B a year (2022) on healthcare. Canada Health Transfers are $49.1B this fiscal year and will grow based on the new funding arrangement. Around $8,500 per person (2022). 12.2% of gross GDP in 2022. Yet there is no clear picture of what is going on, where, or why.

The years of operating without accuracy have resulted in Canada missing on leading and lagging indicators.

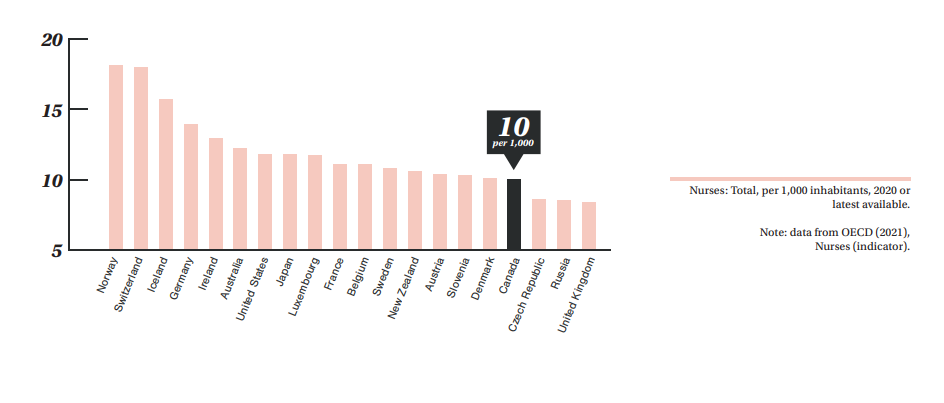

About one-third of registered nurses in 2020 were 50 years old or older. The average age of a physician in the same year was 49. While we are heading into our biggest demand in healthcare with an aging population and mass immigration somehow it was completely lost that our healthcare providers are aging out as well.

It takes years to train medical staff and we arrived at this shortage and demand curve without once along the way doing anything about it within our education system. There also aren’t enough medical facilities for the surge of new immigrants, which also take years to build.

The growth in new medical staff should be coming from encouraging and navigating students into the field in accordance with the education system and government policy. For now, immigration is our lowest-hanging fruit for quickly addressing any shortages. Canada has thousands of immigrants who can’t have their medical credentials and experience tested, another major oversight.

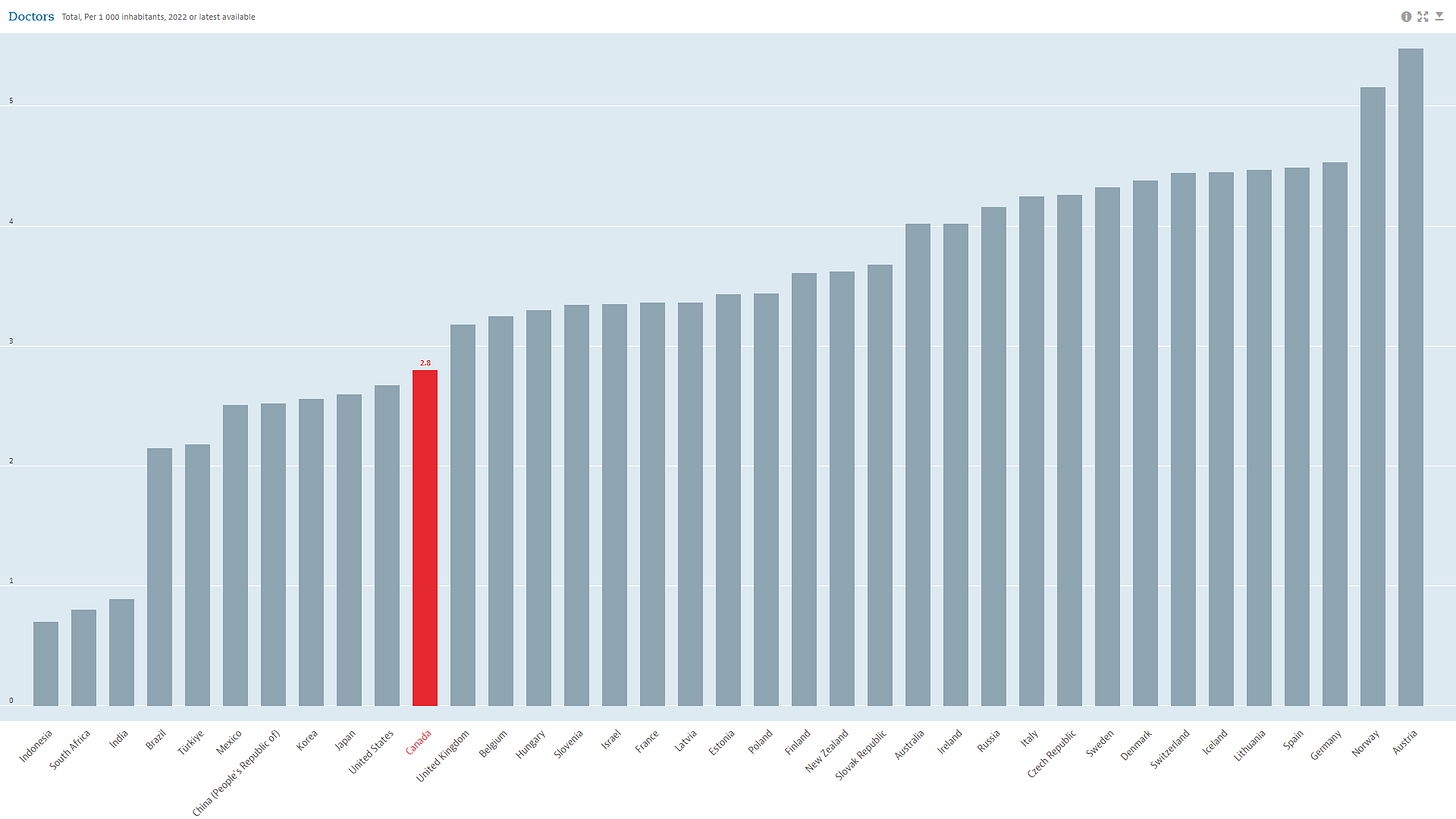

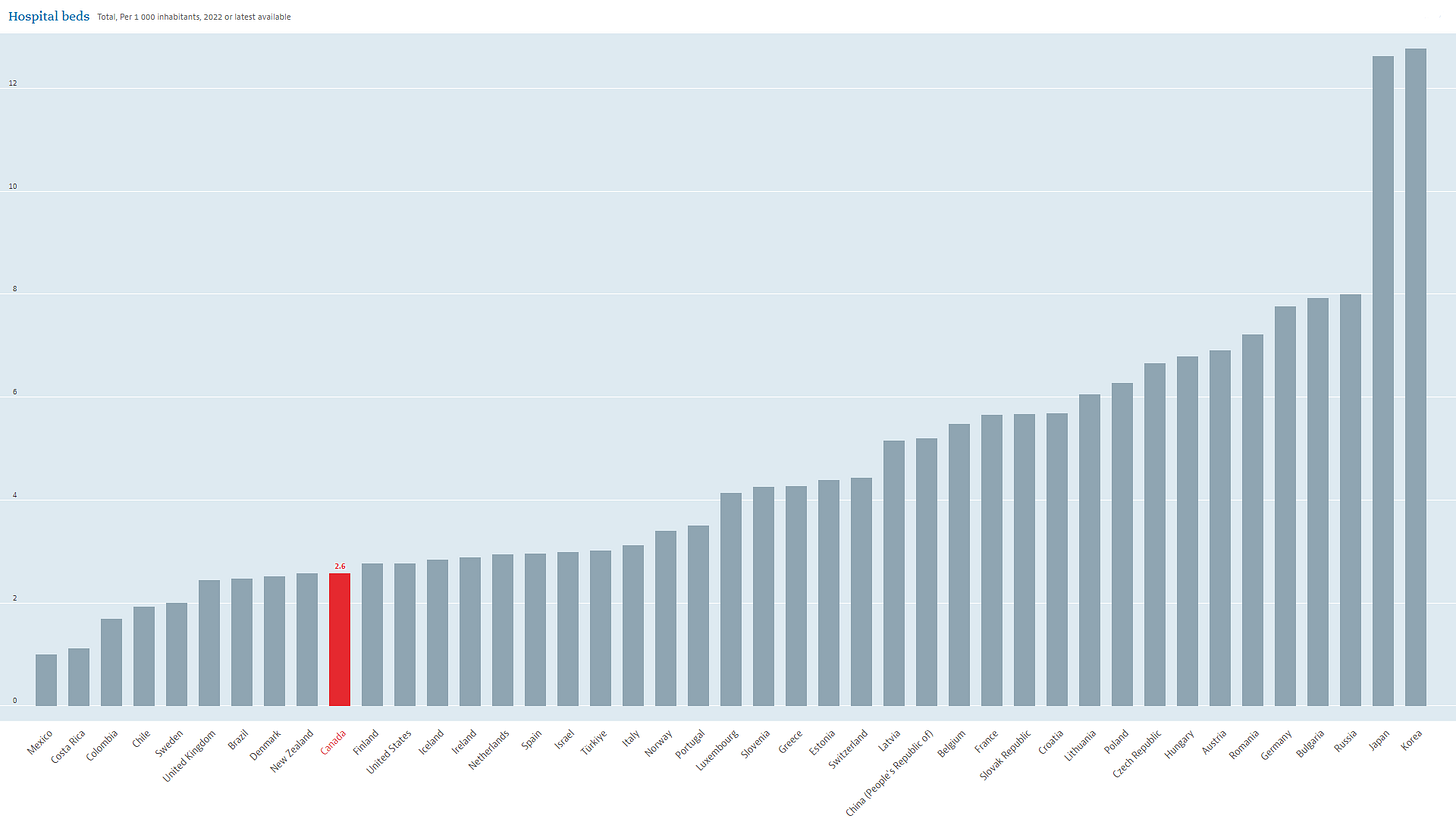

As it is, Canada is lagging behind its peers in medical care with 2.8 doctors per 1,000 people (2022), just under 10 nurses per 1,000 people and the number of beds per 1,000 people has been dropping for years to 2.6.

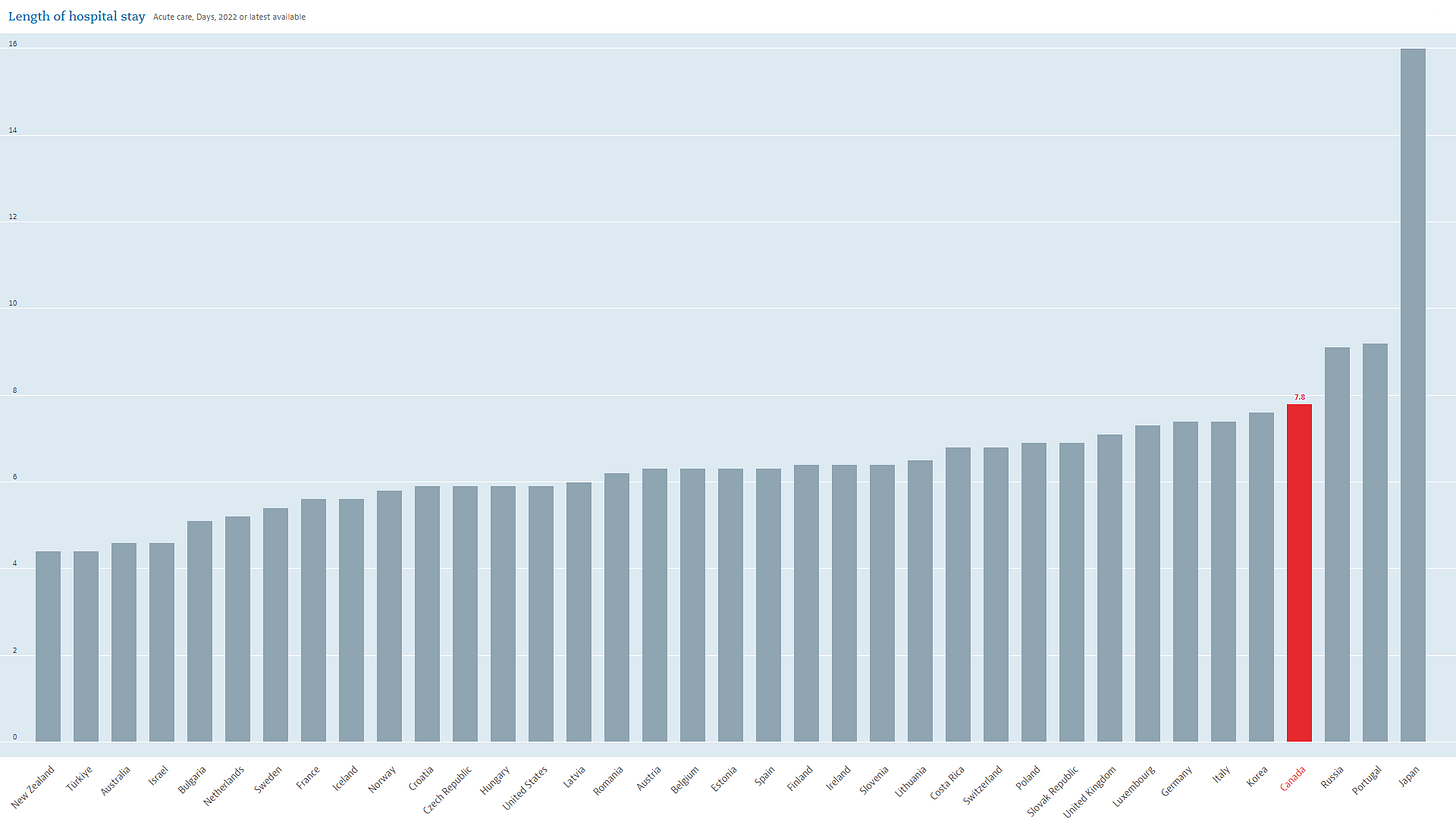

This lack of preparedness and long-term thinking is one of the biggest issues as to why so many Canadians can’t get care and why the wait times are so long. At the same time while not having enough facilities and staff the length of stay in hospitals in Canada is at the high end compared to peers.

Are Canadians staying longer in hospitals because there isn’t enough care? Are they sicker than their peers? Because there isn’t good data we don’t know but some of the major added costs are right here.

The problem with bad or missing data isn’t only impacting the operational execution and performance measurement side but it also has direct consequences to patient care.

The quality and accuracy of continuity of patient care suffer drastically between the analog-digital inconsistent utilization and incur a higher error risk if there is more than one health region involved.

There was the case of Greg Price who died after a complication of surgery. Investigation showed a whole bunch of failures in our healthcare system, disorganization; missed faxes, botched data sharing, urgent scans marked as not urgent, referrals that didn’t happen in a timely matter, etc. (A short educational film was made after his case).

Was Greg’s tragic case malpractice or practice of a hectic unorganized healthcare system? There are tens of thousands of Canadians who die every year from both. It also drives up our costs due to all of these inefficiencies and continued care costs that arose because of needs that weren’t addressed in a timely manner.

While writing this right now, for a month now my doctor can’t get a hold of the surgeon I had a consultation with in regards to new imaging. We had to wait for three weeks extra for my daughter’s referral appointment, after following up with the doctor’s office, turns out the delay happened because their fax machine was broken that day and they forgot to send it out later.

I have to remind you this is 2023.

Canada’s healthcare system must become data-driven with world-class analytics, systems, and communication. That should be where the focus and money be invested.

No one should miss on care because of a missed fax, a typo, or be lost in the system. Because it is 2023.